This exhibition of works from various artists is the third of a series organised by Tin-aw Art Gallery. ‘Back-to-basics’ is the adage that propelled exploration of themes popularly depicted in art. The first two were still life and landscape views. It is good to note that these themes make for subject matter regarded in the past as lowest in a hierarchy where only history, myth, and grand portraiture were worthy of great acclaim. Sweeping changes in the late 17th- and 18th-centuries undermined this order. Changing tastes for art, the influence of new players in the art market, the aims of humanistic education are among forces of change. These are not far removed from those we encounter and experience at present, shifts that alter our being in the world in radical ways.

Few relationships eloquently illustrate this metamorphosis than the one we have with the natural world. We are increasingly at the mercy of an earth burdened by human demands. We have suffered Ondoy and Haiyan, images of their harrowing aftermath haunt us with startling and alarming vividness. It would appear there is no better condition to describe ours than precarious: a constantly threatened existence over which we have little control. We have entered the anthropocene - a period when humans considerably alter the earth’s ecosystems, at a pace never before anticipated. It can be we are plunging headlong into the abyss of another ice age.

Artists explore flora and fauna in works of diverse mediums in this exhibition. Early depictions of flora and fauna can be characterised as colonial device to survey the natural world of far flung colonies. Most well known of the Philippines is Father Blanco’s Flora de Filipinas. Nature is imagined pristine and abundant, to be tamed like the heathens for civilising through the firmaments of religion. Similarly, nature was for plundering to amass wealth funnelled across continents. Melancholy pervades majority of the pieces. In them we sense chaos, anxiety and loss. Nature is imagined as unruly like wayward human behaviour. Sparseness and abundance are placed alongside each other, with emblems that signify species threatened by extinction, or ways of life soon forgotten. To varying degrees, we have become pirates and bandits of nature.

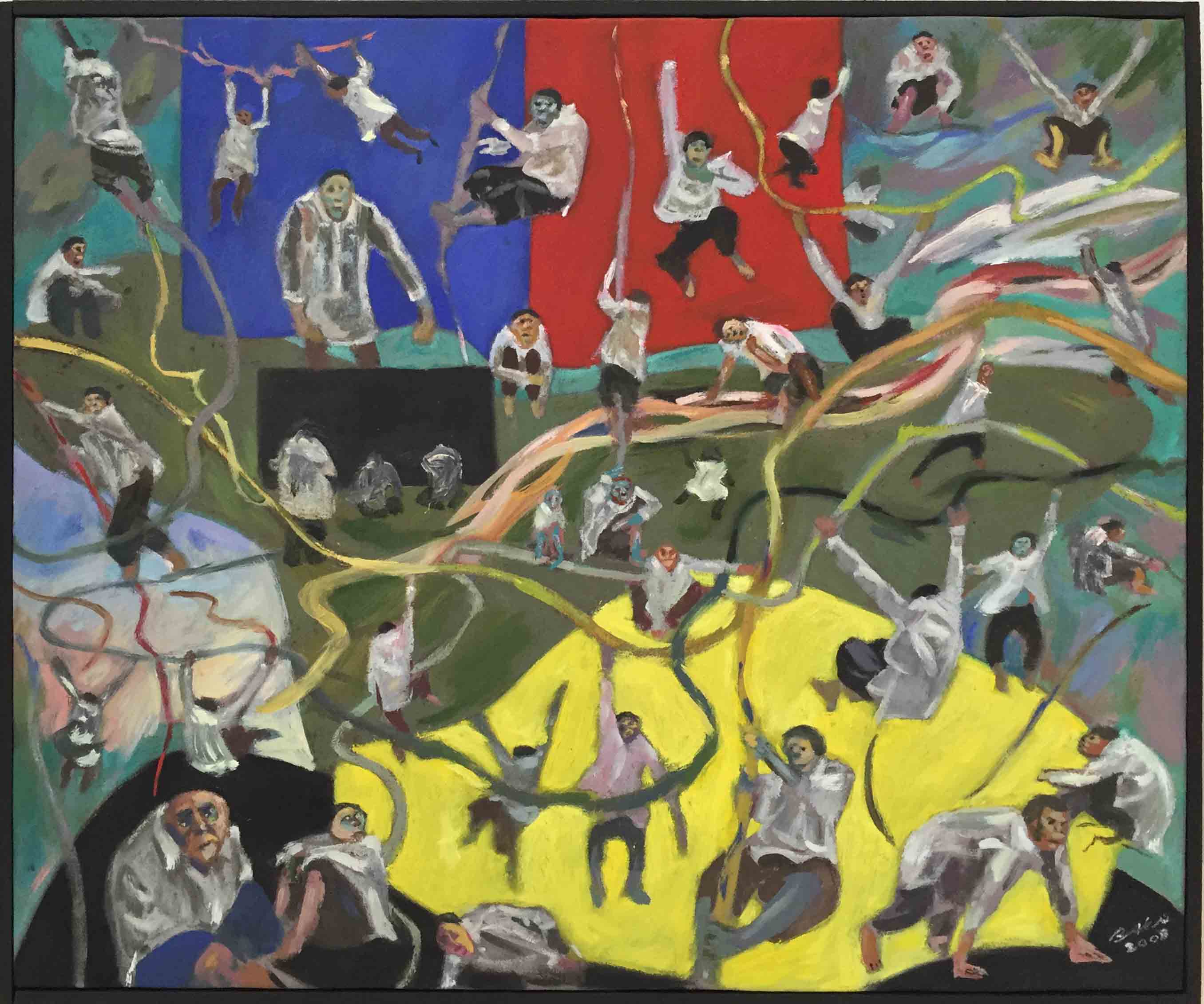

Pablo Baen Santos presents a fitting image of the trap our modern lives have become. He shows a circus of ghoulish baboons springing and swinging to and fro a tangle of vines. We can compare the commotion that pervades the scene with the stagnant air that suffuses the atmosphere of Lee Paje’s piece. Metro Manila’s tangle of traffic can be likened to the snarl at which the figures in Baen Santos’s painting desperately cling. We apprehend two versions of a jungle, an entrapment in the former and the city in the latter. Noli Principe Manalang illustrates this in a straightforward manner. He paints Metro Manila’s skyline inside a gilded cage. The scene emits an effervescent glow alluding to the lure of the city on one hand and the perils of urban life, on the other.

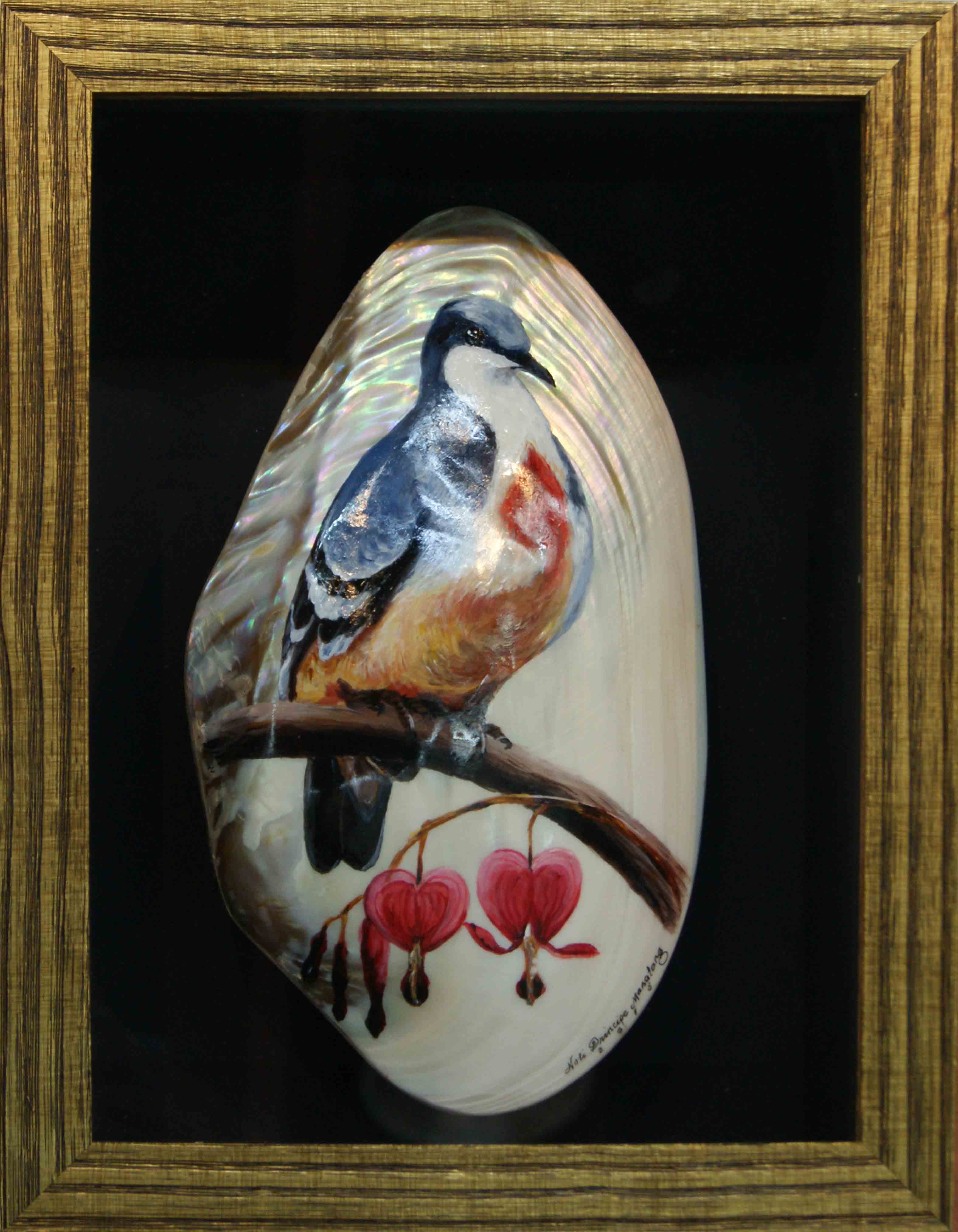

We glean the yearning to keep, preserve, and prolong life from the depictions of birds in Manalang’s other piece. His calcified bird is frozen in time, like taxidermied animals. Life gone is represented by husks of those that were once fervently alive. The same can be said of the prominent detail in Jonathan Ching’s work. Amidst a riot of colourful strokes emerges a brightly hued bird perched on a branch. The strong colours are foil to real birds, which will perhaps later live only in the imaginations of those who have seen them and heard their songs.

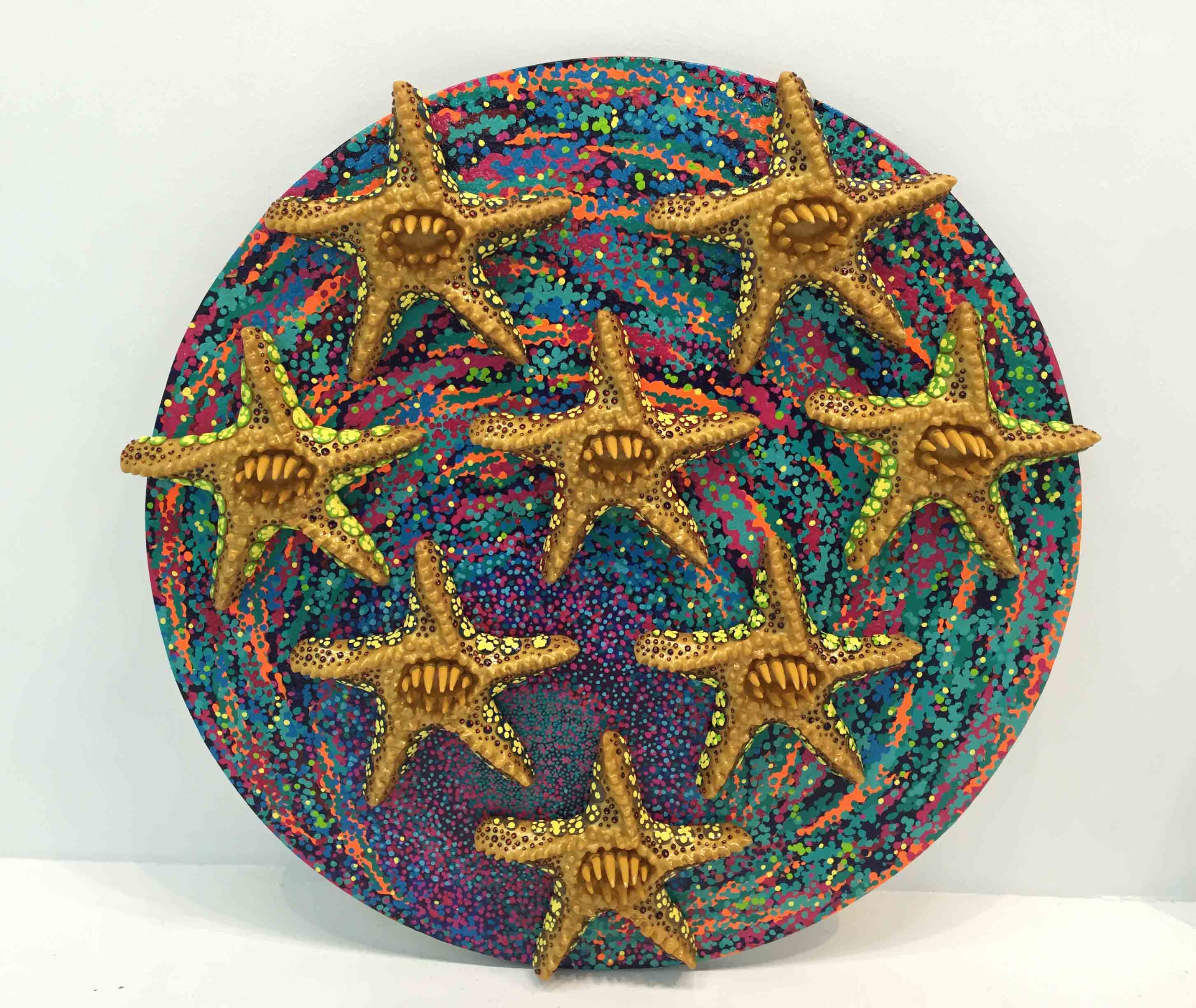

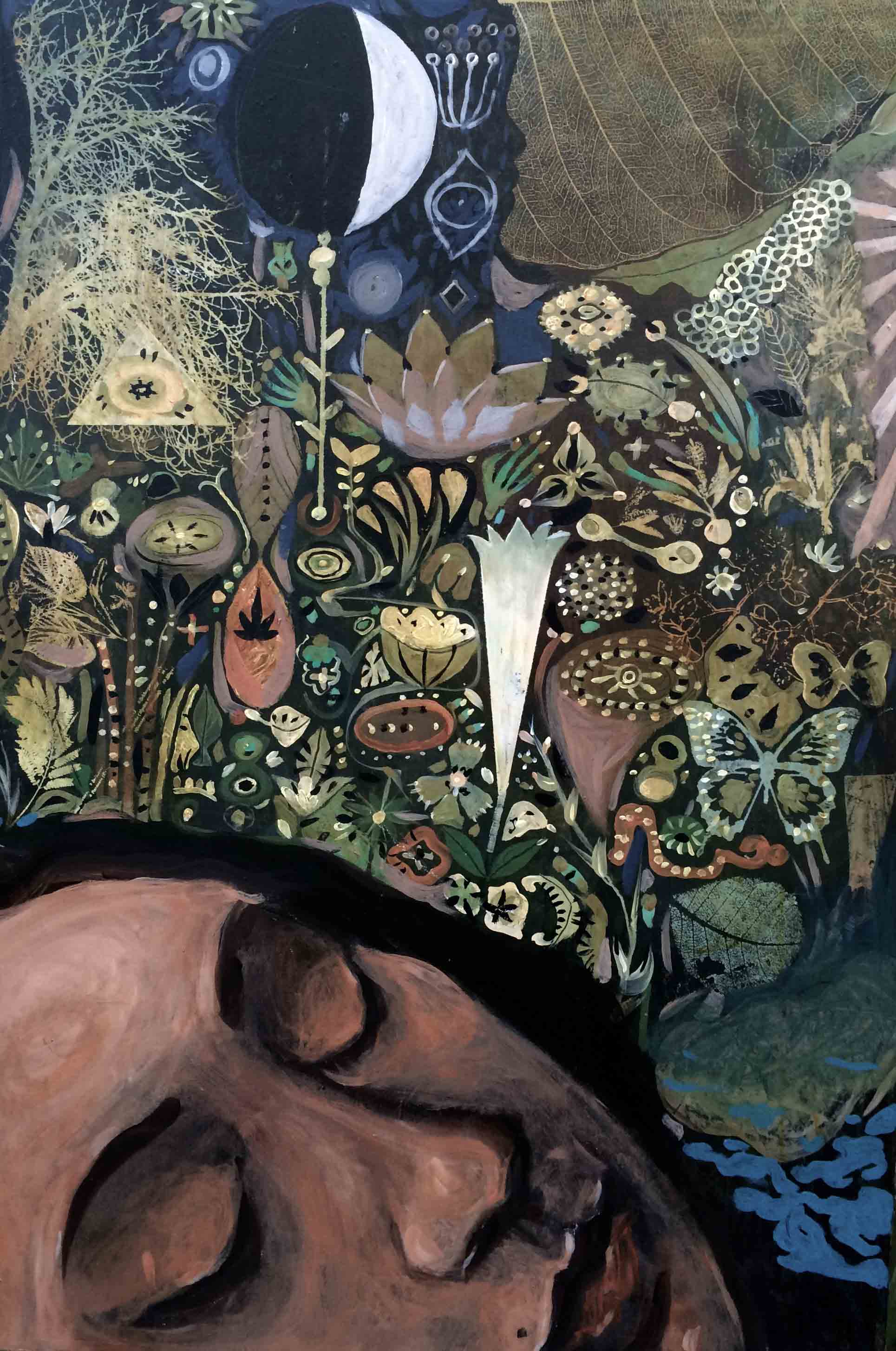

Other pieces essay contrasts between teeming life and scarred, decaying forms. Bree Jonson shows a wounded, skeletal canine whose head is hidden behind a rose bush. It metaphorically channels the pallor of loss and the promise of bloom. Renato Habulan depicts in a pair of paintings lush undergrowth and a fallen tree, destruction in a progression of images. Cian Dayrit’s fossilised animal head appears to have been unearthed from a parched plain, its surface of blackened ridges signifying disastrous practices like oil fracking. Bea Alcala’s and Francis Commeyne’s pieces foretell how remnants of a rapidly perishing natural world are to be presented like specimens in future laboratories where they are cast and catalogued as alien forms. Commeyne’s terrarium of plants cut from discarded soft drink bottles are pale and sparse array of vegetation, collected and housed inside a glass cabinet. Alcala’s brightly coloured meteor with a bevy of starfishes appear otherworldly. On the other, that which remains may only exist in deep reverie, an imagined and far-off place. Anthony Palomo proposes that this may exist only in the embrace of dreams or the realm of the mind.

Channeling characters from the Harry Potter series and playfully titled Mrs. Sprout and the Gamekeeper, this exhibition intimates precarious coupling. The artworks are persuasive depictions of mutation and loss. They contrast decay and rot with fecund and exuberant growth. Most significant is that they vividly capture an ecology greatly altered by humans in irreversible ways. The images ferried by these art works however herald possibilities, for despair like the kind wrought by disasters buoys the human spirit with great force. In a threatened world, a vision of continuity becomes a fount of hope crucial to survival.